Dispatch 2024.3

Series on Industrial Policy in Geoeconomic Restructuring (1 of 4)

A REGULATIONIST PERSPECTIVE ON INDUSTRIAL POLICY IN THE US AND THE EU

By David KARAS

11 April 2024, PDF

The state of the art is at pains to conceptualize capitalist restructuring at the current historical juncture: On the one hand, macro-historical periodization attempts point to an epochal change in interstate relations after US hegemony with concepts such as “the second cold war”, “omni-alignment”, the “crisis of the global liberal order”, “multipolarity”, “polycrisis” (Adler-Nissen & Zarakol, 2021; Lawrence et al., 2024; Mandelbaum, 2024; Schindler et al., 2023). In parallel, a debate is raging within political economy between theories such as the “new state capitalism” which discern new forms of state-market, state-society, and inter-state relations (Alami, 2023), and theories which, on the contrary, stress the hardening of pre-existing hierarchies in all these dimensions (Gabor, 2021, 2023; Wigger, 2019, 2023).

Rejecting the generalizations of both sides in these rupture-continuity debates, I propose a comparative regulationist framework to analyze how change and stasis coexist within different social fields and institutional sub-systems of capitalism at different scales. Applying this framework to industrial policy in the Euro-Atlantic, I show that instead of neoliberal stasis or a global convergence towards a generic model of “state capitalism”, US and EU “green” industrial initiatives represent different processes: whereas the Biden Administration uses industrial policy to recalibrate the US regime of accumulation and its underlying mode of regulation, what unfolds in Europe is a crisis-ridden adaptation of the EU’s transnational mode of regulation, not to displace but on the contrary to preserve a pre-existing regime of export-led accumulation. Finally, I point to the poor international embeddedness of industrial policy initiatives in both the EU and the US.

A Comparative Regulationist Framework

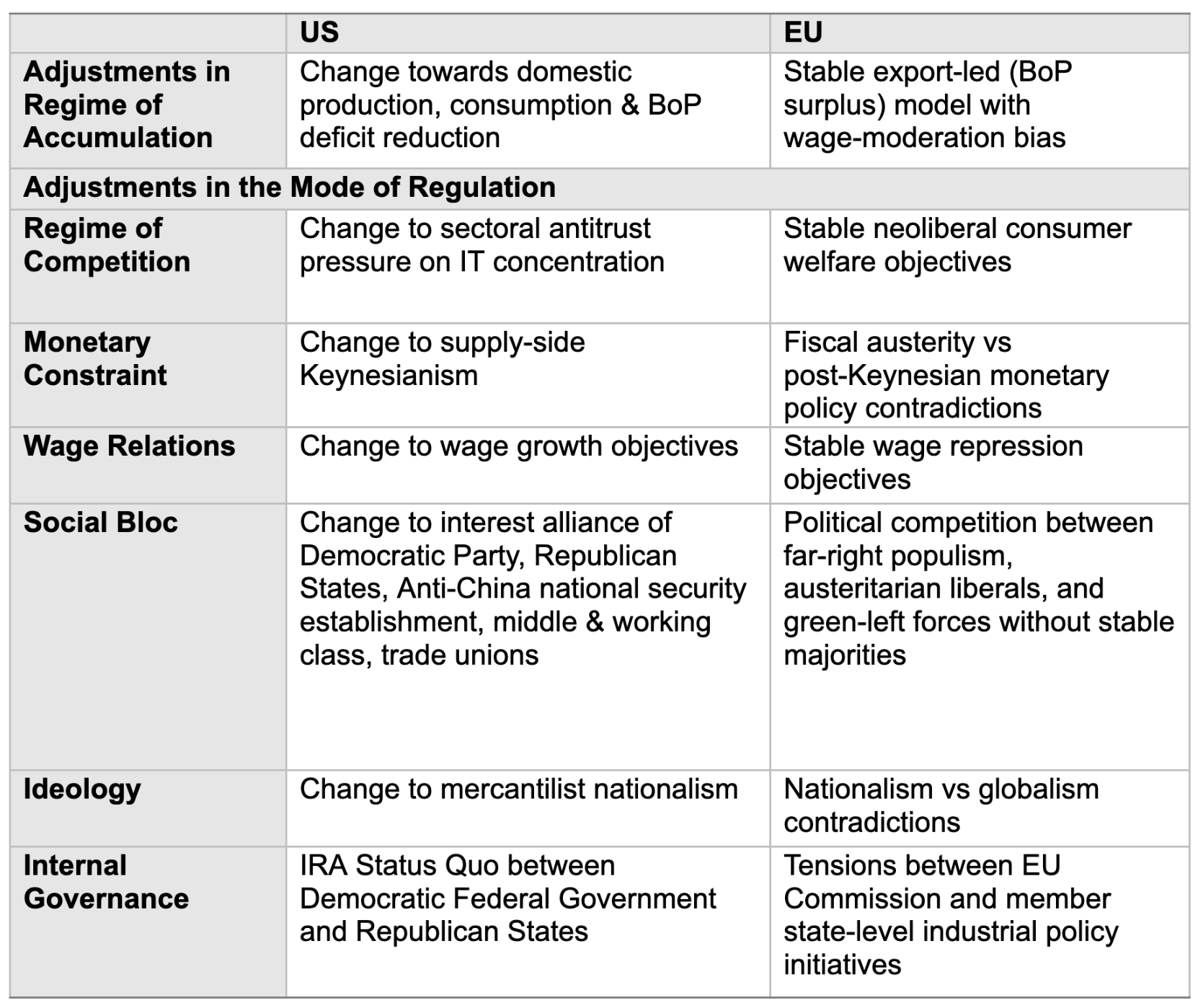

French Regulation Theory (FRT) distinguishes between a regime of accumulation, and the mode of regulation i.e. the political-institutional structures which enable accumulation. The constitutive elements of a mode of regulation were defined as a “regime of competition” (regulating inter-firm relations), the “monetary constraint” (monetary and fiscal policy), and the “wage relation” (the institutional framework of industrial and class relations) (Boyer, 2015, p. 27). Recent FRT applications further added (a) the Gramscian elements of hegemonic ideas, (b) the composition of social blocs stabilizing a given mode of regulation, as well as (c) the transnational modes of governance which coordinate different national forms of capitalism: “the mutual articulation of the transnationally (inter)dependent regimes of accumulation on the one hand and the mode of multi-level regulation that has emerged on the other” (Bieling, Jaeger, & Ryner, 2016). FRT is rooted in a Marxist analysis of capitalism as a crisis-driven, dynamic evolutionary system instead of a stable set of synergetic institutions: in this view, rather than reinforcing one another, institutional, political, ideological, and economic sub-systems often follow separate, and variegated forms of evolution (or stasis), resulting in frequent crises either plaguing the regime of accumulation, its mode of regulation, or the interplay between the two. Any measure of stability is temporary and precarious (Boyer, 2015, p. 58). Applying this framework to US and EU industrial policy initiatives reveals fundamental differences (see table below).

Changing or Keeping the Regime of Accumulation

In the US, the Biden Administration’s industrial policies represent an attempt at recalibrating the regime of accumulation that has supported America’s hegemonic position since 1989. The Washington Consensus cemented the role of the US dollar as a global reserve currency and a financial system based on capital imports flowing from the rest of the world to the US, which filled the US financial sector with capital, fueling financialization and credit-based accumulation (Brenner, 2009; Desai, 2013; Eichengreen, 2008). The price for this position was a deteriorating current account deficit and skyrocketing national debt levels, which, in the long run, weakened the long-term credibility of the dollar as a reserve currency.

A key objective of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is to reverse this process by reshoring industrial production to the US and by subsidizing household consumption for domestically produced industrial goods such as electric vehicles (EVs). The Biden Administration hoped that these measures would improve the current account deficit and alleviate national debt levels while also improving the US dollar’s international credibility. In that regard, Biden has overseen an increase in real wages (US Treasury, 2023) and an improvement in the US current account balance since 2022 (BEA, 2023). However, the IRA, once touted as deficit-reducing, is now expected to increase US government debt (Renshaw, 2023), while global de-dollarization unfolds gradually but steadily (Li, 2024).

In the EU, by contrast, European integration was recalibrated in the mid-1980s as a process aiming for a convergence of diverse European economies toward Germany’s export-led regime of accumulation based on current account surpluses and institutionalized fiscal and monetary austerity (Blyth, 2013; Streeck, 2015). European green industrial policy initiatives today don’t seek to replace this model but to safeguard the EU’s export markets and export competitiveness in a context made ever more difficult by the green transition and US-China rivalries. The German model of export-led growth, which is promoted by the EU for all its member states, shows structural signs of exhaustion, yet neither the EU Commission nor national incumbents in Germany, France, Italy, Scandinavia, or Central Europe are ready to endorse any alternative model of capitalism(s) for the continent (Karas, 2023a).

Adapting the Mode of Regulation

Together with deep alterations to the US regime of accumulation, the Biden Administration used industrial policy to reform the US mode of regulation. Lina Khan’s Federal Trade Commission embodies a new antitrust paradigm (Foroohar, 2024) which deviates from neoliberal consumer welfare justifications, cracking down on market concentration in sectors such as IT and biotech where the US has a strong comparative advantage, while leaving subsidized infant industries such as electric vehicles to prosper. Under the IRA, the monetary constraint to re-industrialization was solved with tax credits managed by the IRS (Fertik, Gabor, Sahay, & Denvir, 2023) instead of nationalizing strategic sectors, unleashing radical fiscal spending, or dramatic tax hikes. Most importantly, industrial policy was used by Biden to counter the Trumpian populist revolt and broaden the Democrats’ shrinking electoral base beyond college-educated urbanites (Gethin, Martinez-Toledano, & Piketty, 2022). To this end, the IRA rests on a fragile but far-reaching bipartisan cross-class alliance that offered dividends to middle and working classes, trade unions, Republican-controlled red states, and anti-China national security hawks (Karas, 2023b).

In Europe by contrast, attempts to adapt the EU’s mode of regulation sustaining export-led growth have resulted in political, ideological, and institutional tensions. The EU inherited from the 1980s a neoliberal competition policy apparatus as well as the dogma of fiscal and monetary austerity, whose imposition to all member states became the leitmotiv of European integration throughout the 1990s (Scharpf, 1999). However, they now curtail vertical, sector-specific industrial policies necessary to defend European export competitiveness. Austeritarians resist public spending, while member states and the Commission distrust each other: Member states fear the Commission’s attempts at Europeanizing industrial policy with a dedicated supranational fund and administration would limit national competencies. Many in the Commission conversely see member states lobbying for industrial policy exemptions from existing EU competition and fiscal rules as the first step towards European disintegration.

This stalemate has resulted in a lack of coordination between industrial initiatives steered by supranational EU bureaucracies and national governments. In the electric battery sector, for instance, the Commission’s PPP model of cooperation with startups such as Swedish Northvolt contrasts with large-scale governmental subsidies in France and Germany for national legacy car makers to develop their in-house batteries or with Hungary’s strategy to attract via FDI an entire East Asian e-battery ecosystem. Unlike the US, there hasn’t been any concerted effort by European incumbents to use industrial policy as a strategy to fence off the far right or engineer a broader class compromise. Whereas Biden emphatically supported UAW worker strikes, European adherence to export-led growth relies on wage repression (Wigger, 2023). However, endemic labor shortages undermine wage repression in green industrial sectors such as electric cars, electric batteries, or renewables (Karas, 2023b): instead of improving the bargaining position of workers, increasingly anti-immigration governments (Vohra, 2023)respond by importing tightly monitored temporary workers from the Global South’s reserve army of labor to keep wages and unionization at bay (Czirfusz, 2023).

Poor International Embeddedness

A comparative regulationist perspective shows that underneath superficial similarities, industrial policy represents different forms of capitalist restructuring in the US and EU. The two processes are, however, connected, and both US and EU industrial policies suffer from design flaws in how they are internationally embedded.

A core geopolitical objective behind US industrial initiatives such as the IRA is to cut off China from American technology and capital, whereas the EU’s export-led regime relies on Chinese inputs and access to China’s export market. It is thus precisely the American decision to recalibrate its regime of accumulation away from Chinese interdependence, which is now choking the EU’s export-led regime of accumulation and forces desperate attempts to adapt the EU’s multi-level mode of regulation to this new reality.

However, US industrial policy is also poorly articulated with foreign policy objectives: it offers few benefits for US allies in Europe or Asia, nor does it provide a developmental roadmap to facilitate industrialization and value-chain upgrading for the Global South. US efforts to prevent Chinese firms from accessing IRA subsidies also run into limits abroad. As Chinese firms build factories in strategic sectors such as electric batteries in countries that have privileged trade relations with the US in Europe (Germany, France, Hungary), Latin America (Mexico), Asia (South Korea), Africa (Morocco), it becomes diplomatically increasingly costly for the US to enforce anti-Chinese regulations on inputs sourced from allies. The paradox is that the anti-Chinese bent of US industrial policy, which is politically vital in mobilizing bipartisan political support for the IRA at home, is a weakness for US geopolitical ambitions as it alienates external partners. The effective enforcement of anti-China rules would necessitate international cooperation to be meaningfully implemented across global supply chains: a distant prospect as it contradicts the fundamental interests of even the closest US allies such as the EU.

—

David Karas is a French-Hungarian political economist who studies the changing roles of the state in the era of climate crisis, geoeconomic competition, industrial policy, financialization, and post-neoliberal developmental trajectories in developing economies. He is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the CEU Democracy Institute in Budapest.

References

Adler-Nissen, R., & Zarakol, A. (2021). Struggles for Recognition: The Liberal International Order and the Merger of Its Discontents. International Organization, 75(2), 611-634.

Alami, I. (2023). Ten Theses on the New State Capitalism and its Futures. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space.

BEA. (2023). U.S. Current-Account Deficit Narrows in 3rd Quarter 2023 [Press release].

Bieling, H.-J., Jaeger, J., & Ryner, M. (2016). Regulation Theory and the Political Economy of the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(1), 53-69.

Blyth, M. (2013). Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boyer, R. (2015). Économie politique des capitalismes. Théorie de la régulation et des crises. Paris: La Découverte.

Brenner, R. (2009). What Is Good for Goldman Sachs Is Good for America. The Origins of the Current Crisis.

Czirfusz, M. (2023). The Battery Boom in Hungary: Companies of the Value Chain, Outlooks for Workers and Trade Unions.

Desai, R. (2013). Geopolitical Economy After US Hegemony, Globalization and Empire. London: Pluto Press.

Eichengreen, B. (2008). Globalizing Capital. A History of the International Monetary System. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fertik, T., Gabor, D., Sahay, T., & Denvir, D. (2023). Defining Bidenomics. Phenomenal World.

Foroohar, R. (2024). The Great US-Europe Antitrust Divide. Financial Times.

Gabor, D. (2021). The Wall Street Consensus. Development and Change, 0(0), 1-31.

Gabor, D. (2023). The (European) Derisking State. Stato e mercato, 43(1), 53-84.

Gethin, A., Martinez-Toledano, C., & Piketty, T. (2022). Brahmin Left versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages in 21 Western Democracies 1948-2020. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(1).

Karas, D. (2023a). Germany’s Model for European Capitalism is Exhausted. Jacobin.

Karas, D. (2023b). Industrial Policy isn’t a Panacea for Rebuilding Organized Labor. Jacobin.

Lawrence, M., Homer-Dixon, T., Janzwood, S., Rockstoem, J., Renn, O., & Donges, J. (2024). Global Polycrisis: The Causal Mechanisms of Crisis Entanglement. Global Sustainability, 1-36. doi:10.1017/sus.2024.1

Li, Y. (2024). The Dollar Still Dominates, but De-Dollarization Is Unstoppable. International Banker.

Mandelbaum, H. G. (2024). Brazil in the “Second” Cold War: Navigating the US-China Fault Lines. Dispatches of the Second Cold War Obsevatory.

Renshaw, J. (2023). Biden’s IRA Climate Bill Won’t Cut Deficit As Expected. Reuters.

Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe: effective and democratic? Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Schindler, S., Alami, I., DiCarlo, J., Jepson, N., Rolf, S., Bayırbağ, M. K., . . . Zhao, Y. (2023). The Second Cold War: US-China Competition for Centrality in Infrastructure, Digital, Production, and Finance Networks. Geopolitics.

Streeck, W. (2015). The Rise of the European Consolidation State. MPIfG Discussion Paper 15(1).

US Treasury. (2023). The Purchasing Power of American Households [Press release].

Vohra, A. (2023). The Far Right Is Winning Europe’s Immigration Debate. Foreign Policy.

Wigger, A. (2019). The New EU Industrial Policy: Authoritarian Neoliberal Structural Adjustment and the Case for Alternatives. Globalizations, 16(3), 353-369.

Wigger, A. (2023). The New EU Industrial Policy and Deepening Structural Asymmetries: Smart Specialisation Not So Smart. Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(1), 20-37.